Tender Choice

One of the fundamental benefits we see from a cat is the ability to carry a capable, easily launched tender. For us, that means:

- Tough rigid hull

- Big enough to carry up to 6 people

- Reasonably dry ride

- Able to plane and cover a few miles quickly

The balancing factor is weight. We’d also like our tender to be:

- Light enough to pull up a beach

- Light as possible to minimise effect on the mothership when in the davits

Aluminium hulled RIBs tend to be the most popular choice for multihull tenders but a more recent breed of carbon composite boats is gaining popularity, so we had a good look at some options. Here’s a comparison table:

| Model | Material | Weight | Payload |

| 3D Tender – Ultralight 330 | Aluminium / PVC or Hypalon | 41kg | 550kg |

| Highfield – Ultralight 310 | Aluminium / PVC or Hypalon | 50kg | 585kg |

| Highfield – Ultralight 340 | Aluminium / PVC or Hypalon | 53kg | 663kg |

| AB – Lammina 10AL 319 | Aluminium / Hypalon | 53kg | |

| OC 350 | GRP – glass or carbon | 54 / 44kg | 448kg |

| AST 340 | GRP – glass & carbon | 39kg | 480kg |

I didn’t know the 3D Tender range but a mate who has a 3D recommended them. Their Ultralight 330 model gives the size and payload we need, yet it’s almost 20% lighter than the most comparable Highfield (which is admittedly wider but shorter, with a slightly higher payload). In fact, the 3D is only 2kg heavier than the lightest carbon tender and has a higher payload, tough hull (although the inflatable tubes are more vulnerable) and a relatively dry ride. http://www.3dtender.com

It’s also the lowest price of all the above options. I’m still wondering what the catch will be… but we’ve bought one (now called Derek in a nod to his stowage location) and it looks well made to me.

Derek doesn’t have a double, flat floor (maybe we’ll add a light composite floorboard to keep kit above any accumulated bilge water) but he does have a lockable bow locker which will be great for fuel, anchor and any other small stuff left aboard while ashore. We’ll fit fold-down transom wheels to make it easier to pull him up a hard beach.

Our controversial decision is probably the tube material and I’m braced to be told I’ve been daft. We’ve gone for Valmorel PVC rather their Hypalon option because Hypalon seams have to be glued, whereas PVC seams can be welded. Word is that glued seams are often the first thing to fail. Valmorel PVC is reputed to be a big step forward from older PVCs – apparently it doesn’t go sticky and break down in the sun.

We’ve just made a tubes cover (for some reason known as dinghy “chaps” – why?!) and, to be honest, are rather proud.

A few years ago Amanda bought a Sailrite sewing machine, made an all over sun-protection cover for our Pogo, Rush  and has recently been working down the size range but up the complexity scale. Chaps are (hopefully) about as curvy and tricky as boat cover making gets! Seems cover making is another unexpected upside to recent travel restrictions, a boat in build and time at home!

and has recently been working down the size range but up the complexity scale. Chaps are (hopefully) about as curvy and tricky as boat cover making gets! Seems cover making is another unexpected upside to recent travel restrictions, a boat in build and time at home!

Anyway, we’ll also make a full top cover to use when Derek is in the davits so, with that and the chaps, the PVC tubes should see little direct sun and will hopefully prove the right choice…

There isn’t a 3D Tender dealer in South Africa, so we bought Derek from Ocean First Marine in the UK and we’ll ship him, with a load of other gear, out to CM.

Outboard motor

I’ve been mulling over outboard choice. It’s tempting to buy a 15hp 2-stroke in South Africa, where they’re still available. It would be 25% (11kg) lighter than the equivalent 4-stroke and simpler to service. But 2-strokes are a bit louder and less “clean”. That said, I gather modern 2-strokes are better than older designs on both fronts so am hoping the differences will not be meaningful and am leaning that way.

The Suzuki 15hp is the lightest on the market at 33kg, using the same platform as their 9.9hp. We have a larger 4-stroke Suzuki outboard on a 6m RIB at home which has proved extremely reliable so we’re happy to stick with the brand. And they’re black which is, of course, crucial to the decision / colour scheme. The plan is to order the outboard from a dealer close to CM and Julian has offered negotiate a local’s rate deal.

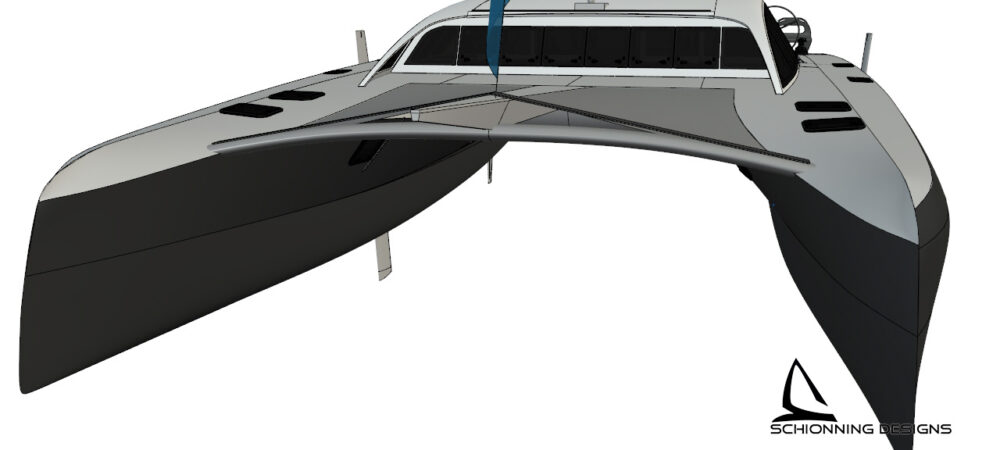

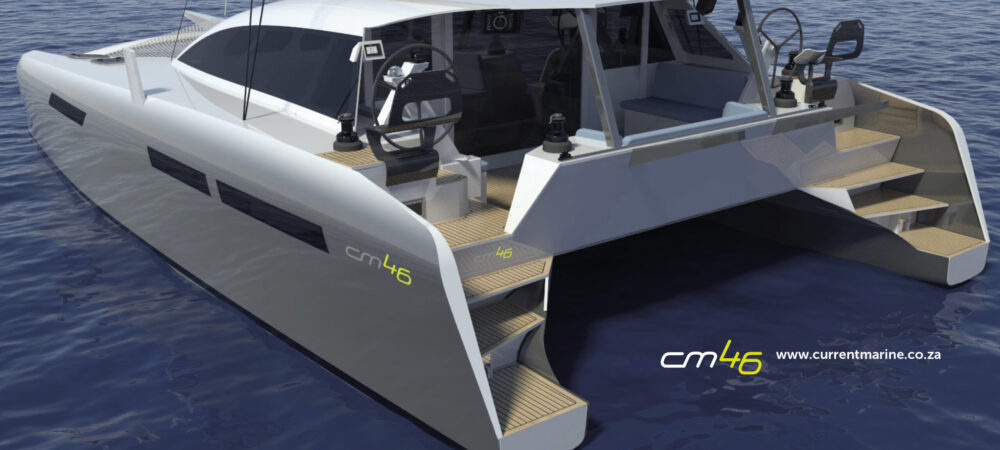

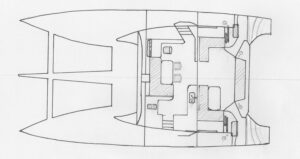

It prioritises galley space and stowage, which is up-there with heavier, fatter cats of this length.

It prioritises galley space and stowage, which is up-there with heavier, fatter cats of this length.